As widely anticipated, the US Federal Reserve has cut its key Fed Funds cash rate by 0.25% to a range of 2-2.25%. This is the Fed’s first rate cut since December 2008 and follows nine 0.25% rate hikes between December 2015 and December last year. The Fed also announced that quantitative tightening (ie the process of reversing its quantitative easing program by letting bonds on its balance sheet mature) will end immediately, which is about two months earlier than previously flagged. The Fed’s post-meeting statement left the door open to more cuts although Fed Chair Powell’s press conference confused things a bit (again!) by saying it’s a “mid-cycle adjustment” and “not the beginning of a long series of cuts” but it may not be “just one”.

Taking out some insurance

With underlying US growth still solid and the jobs market tight this should be seen as the Fed taking out some insurance given various threats to the growth outlook including from the US/China trade war, tensions with Iran and slower global growth generally and a greater willingness by the Fed to take risks with higher inflation as opposed to deflation.

So it’s a bit like the easings of 1987 after the share market crash and in 1998 during the LTCM hedge fund crisis when Russia defaulted leading LTCM to go bust, threatening the US financial system.

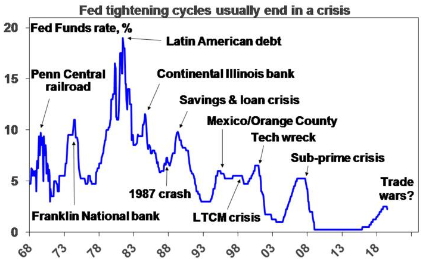

The pattern of the past 50 years or so is for the Fed to cut rates after some form of crisis threatens the economic outlook. See the next chart. In 2001 it was the tech wreck and in 2007 it was the sub-prime mortgage crisis. This time around there is nothing on that scale although it may be argued that the trade wars are providing the biggest single threat.

Source: Thomson Financial, AMP Capital Investors

This year’s fall in core private final consumption inflation back below the Fed’s 2% target provided the Fed with the scope to move.

Further easing is likely, but it’s likely to be limited

It’s rare for the Fed to just cut once. In the insurance cuts of 1998 through the LTCM crisis it eased 3 times by 0.25%. Given that the risks to the growth outlook – particularly on trade – won’t go away quickly and that the Fed appears to have taken the decision that it’s easier to control a rise in inflation than a further slide or deflation, it’s likely to cut rates further and we are allowing for another cut in September.

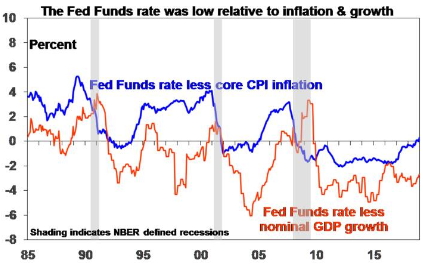

However, we remain of the view that a US recession is not imminent (see The longest US economic expansion ever). While the yield curve is flashing warning signs, the excesses that normally precede US recessions are not present. In particular: the US has not seen a spending boom with cyclical spending on consumer goods, investment and housing running around average as a share of GDP; private debt growth has been moderate; and inflation has been low. Consequently, there is no boom to go bust. Moreover, monetary policy had not become tight with the Fed Funds rate never having reached the high levels that normally precede recessions. See the next chart.

Source: NBER, Bloomberg, AMP Capital

As a result, we see this easing cycle by the Fed as being limited to around 2 or 3 rate cuts with the next likely coming in September as opposed to the 4 or so that the money market has factored in.

Of course, the main threats to this relate to US trade wars and tensions with Iran.

The Fed and shares

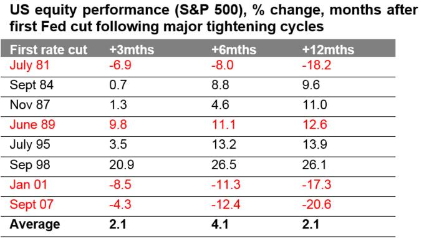

Falling interest rates are generally positive for shares. They help boost economic and profit growth and make shares relatively more attractive than cash and hence are usually associated with a higher price to earnings multiples. The table below shows the US share market’s response after the first-rate cut following major tightening cycles.

US recession highlighted in red. Source: Thomson Reuters, AMP Capital

The US share market rose over the subsequent 3, 6 and 12 months after the commencement of 5 of the last 8 Fed easing cycles. The exceptions were after the rate cuts in 1981, 2001 and 2007 which were associated with recessions.

The reaction by the Australian share market is similar, except the Australian share market wasn’t greatly affected by the post-2000 bursting of the tech bubble.

US recessions highlighted in red. Source: Thomson Reuters, AMP Capital

So if we are right and the US avoids a recession in the next year or so then US interest rate cuts should be positive for shares beyond any near term uncertainty (and the initial reaction which has seen US shares fall as the Fed wasn’t as dovish as hoped) and are likely to be higher on a 6-12 month horizon. It is worth repeating the old saying “don’t fight the Fed”. While scepticism is high that central banks with low-interest rates and QE will spur growth, an investor would have made a huge mistake over the past decade betting against them. The key though is that global economic indicators need to start improving in the months ahead.

Implications for Australian interest rates

The directional relationship between the US and Australian interest rates weakened long ago. The RBA started raising rates in 2009 when the Fed held at zero, it was easing in 2016 when the Fed was hiking and this year it started cutting ahead of the Fed. So just because the Fed moves doesn’t mean the RBA will as well! On the one hand the Fed’s easing along with stimulus elsewhere globally should help support global growth which is good for Australia. But it’s probably not enough to change the outlook for the RBA. Our view remains that it’s on track to cut the cash rate to 0.5% by early next year and to some degree the Fed cutting too reinforces that to the extent that the RBA would like to keep the Australian dollar down.

What about the role of President Trump?

President Trump has been highly critical of Fed rate hikes over the past year and has been saying they should be cutting in recent times. Of course, presidents and prime ministers usually prefer lower than higher rates but the issue, in this case, has been more around whether his comments represent a threat to the Fed’s independence, which is necessary to ensure sensible monetary policy as opposed to politically driven moves. In a world of increasing populism, this could become more of an issue. In terms of the role he may have played in the Fed’s latest decision it’s likely that the Fed has made up its own mind but it’s also interesting to note that President Trump’s huge fiscal easing last year likely played a role in Fed hikes last year and now his escalating trade war has played a role in its easing! So, one way or another he had an impact.

If you would like to discuss any of the issues raised by Dr Oliver, please call on 07 4052 8200 or email enquiries@vpfs.com.au.

Author: Dr Shane Oliver, Head of Investment Strategy and Chief Economist

Source: AMP Capital 01 August 2019

Important notes: While every care has been taken in the preparation of this article, AMP Capital Investors Limited (ABN 59 001 777 591, AFSL 232497) and AMP Capital Funds Management Limited (ABN 15 159 557 721, AFSL 426455) (AMP Capital) makes no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or completeness of any statement in it including, without limitation, any forecasts. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This article has been prepared for the purpose of providing general information, without taking account of any particular investor’s objectives, financial situation or needs. An investor should, before making any investment decisions, consider the appropriateness of the information in this article, and seek professional advice, having regard to the investor’s objectives, financial situation and needs. This article is solely for the use of the party to whom it is provided and must not be provided to any other person or entity without the express written consent of AMP Capital.